Now folks this is a rare treat! Alan Toelle has responded to some questions concerning the French multi colour camouflage and I quote him here.

"French 1918 Camouflage Scheme

I will try to address the questions regarding 1918 French Camouflage that have been raised in the foregoing discussion.

The basic technology as described in the Cross & Cockade Project Butterfly series was based on direct quotations from contemporary technical reports, and remains valid today as it was then. That information was augmented by the study of a number of original specimens. That work was conducted in the laboratory of Dr. Robert L. Feller of the National Gallery of Art Research Project, Mellon Institution. He confirmed that the airplane coating met the standards as described in the technical literature, and that the pigmentation was the same. Based on that, I obtained the various pigments and, by trial and error, determined the proportions that would reproduce the colors seen on the original specimens that I had in hand at that time.

Since that time (35 years), I have been all over the USA, France, Belgium, and Italy, and have seen some 200 original specimens of this material. I also now have some 100 specimens in hand, and have made cross sections of many of them for examination under the microscope. All this has only confirmed most of the earlier work.

Regarding camouflage patterns, airplane production, manufacturers, etc., a great deal of new information has been obtained, and the ability of illustrating it has improved many-fold. The results of this research is evident in publications of the past six years, including Ted Hamady’s Nieuport 28 book, my own Breguet 14 Datafile, Tomasz Groncewski’s book on the Spad VII, Flying Machine Press’ Salmson Aircraft of World War I, and other illustrations by Juanita Franzi, Ronny Bar, and myself, appearing in Over the Front and Windsock. A Datafile on the Spad XII cannon is also well along. Therefore, the Project butterfly illustrations do not represent the latest or best source of information.

Fabric surfaces:

The fabric surfaces received four coats of cellulose-acetate dope. The first and 4th coat were clear, and the 2nd and 3rd coats pigmented. The pigmentation of the camouflage colors contained 42% by weight aluminum powder. The black color sometimes did not contain aluminum powder. The resulting surface was generally not flat, but was slightly undulating according to the weave of the fabric. Sometimes, however, it turned out nearly flat. The tendency was probably toward less dope rather than more.

The aluminum powder was in a non-leafing flake form. The flakes were produced in a ball mill, which resulted in irregular size and shape, somewhat battered in appearance, but generally flattened. In the coating, the flakes take a generally horizontal orientation as the coating dries. The flakes are never at the surface, but are distributed down in the coating. The flakes are not in contact with one another or packed together. They sometimes overlap but are not necessarily continuous. The colored pigments are very finely ground compared to the aluminum flakes. The resulting coating, when viewed under the microscope from the face, has the character of depth, the matrix being colored with flakes appearing colored depending on their depth in the coating. In cross section, the flakes appear as thin bright more-or-less horizontal streaks.

To the naked eye, the coating is reflective and sensitive to the illumination and angle of incidence. As with plain aluminum coatings, the camouflage dopes also exhibit the character known as “flop.” This causes the coating switch from dark to light with a slight change of angle of incidence of the illumination. This phenomenon is quite evident on aluminum-doped Nieuport 17s, where the fuselage sides often appear to be painted with a completely different dark color. Also, on Nieuport 28s having many facets, with certain illumination and viewed from above, the fuselage seems to have one of the stringers caved in. The phenomenon occurs when rays of light get trapped within the coating and dissipate by bouncing off the bottom of adjacent flakes instead of back to the viewer.

The most appropriate description of the appearance of the coating is that of a wet fish. It is not glossy, but neither is it matte. It is reflective or dull depending on the illumination. It has depth.

The camouflage dopes were patented, but were produced under license by a number of manufacturers. The colors vary a bit, but each color stays within a certain tolerable range. They are not a continuum from one color to another. They have distinctively different pigmentation.

Research done by the Memorial Flight is said to have discovered the use of other metal powder(s). But I personally have seen only aluminum, which is very easy to identify under the microscope. Simply expose it to a drop of caustic and it is quickly destroyed!

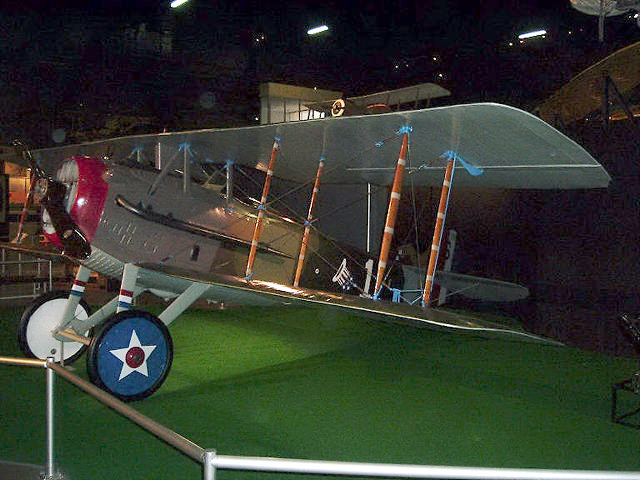

Of the photos posted on this thread, that of the right side of Frank Luke’s 27th Aero Squadron plane displays the most-correct colors. It is extremely difficult to photograph these airplanes in museums as the various sources of lighting distort the color.

Undersurface color:

The contemporary literature all mentions bleuté or blanc-bleuté for the undersurface color. But virtually all original specimens I have seen are écru, a word meaning raw, unbleached, or natural, but also representing the color of old computers. This is not some aged example of bleuté, but rather an intentional pigmented color. I found ecru on numerous Spad, Breguet, Salmson, and Nieuport 28 specimens. I have only discovered one example of blanc-bleuté, a fragment of fabric clinging to an uncovered tailplane from SPAD-built Spad XIII S.757 constructed in early 1918. It is pigmented with aluminum powder and a white extender. There may be a very small amount of blue pigment. But it is basically a very light silvery-gray color. So, the basic conclusion I reach is that ecru was by far more common color, but SPAD used blanc-bleuté. I presume others did as well, but don’t have any data.

Solid and metal parts:

The solid and metal parts were painted with “Ripolin.” This is a trade name but also used generically to describe a high-grade oil-based paint. Gertrude Stein reported that Pablo Picasso, and other artists of that time (ca. WW-1), used Ripolin instead of artists colors because it was a lot less expensive. Ripolin was produced in a variety of colors that corresponded approximately to the colors used on the fabric surfaces. It did not contain aluminum powder. From original specimens I have seen, I would describe it as semi-gloss. It was definitely not matt. It was specified for wheel discs. I don’t have any empirical data on the composition of Ripolin.

Cocardes:

It was permitted to use either Ripolin or colored dope. I have seen examples of both. I don’t know of any general rule. The colors used on cocardes varied a great deal, especially the blue. Original specimens associated with particular manufacturers are rare.

Alan Toelle"